- Home

- Richard B Mead

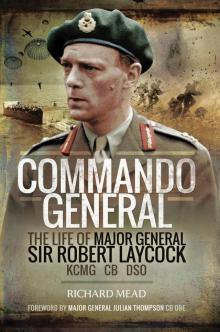

Commando General

Commando General Read online

Commando General

Commando General

The Life of Major General Sir Robert Laycock KCMG, CB, DSO

Richard Mead

Foreword by Major General

Julian Thompson CB, OBE

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright © Richard Mead 2016

ISBN 978 1 47385 407 9

eISBN 978 1 47385 408 6

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47385 409 3

The right of Richard Mead to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

List of Maps

Foreword

Introduction

Prologue

Chapter 1 Joe

Chapter 2 Bob

Chapter 3 Blues

Chapter 4 Barque

Chapter 5 Angie

Chapter 6 Gas

Chapter 7 Commando

Chapter 8 Training

Chapter 9 Layforce

Chapter 10 Bardia

Chapter 11 Crete

Chapter 12 Disbandment

Chapter 13 Flipper

Chapter 14 Brigade

Chapter 15 Reorganization

Chapter 16 Husky

Chapter 17 Avalanche

Chapter 18 COHQ

Chapter 19 Chief

Chapter 20 Peace

Chapter 21 Malta

Chapter 22 Sunset

Chapter 23 Reflections

Appendix: Directive to the Chief of Combined Operations 28 November 1943

Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

Sources and Bibliography

Notes

List of Maps

1. The Eastern Mediterranean

2. Crete – The Road to Sphakia

3. Eastern Sicily

4. Salerno

Foreword

Robert Laycock was the youngest British or Commonwealth officer to be promoted to the rank of major general in the Second World War, at the age of thirty-six. But as Richard Mead tells us, ‘Bob’, as he calls him, ‘never went on to higher command in the field or in grand strategy’, so he cannot be counted among the truly great soldiers of the Second World War. Instead, Richard Mead believes, with good reason, that Laycock deserves to be remembered for his key role in the evolution of the Commandos from their tentative beginnings into the elite formation they are today. He was one of the first Commandos, and it is to his credit that the inheritors of the concept launched in June 1940, are the Royal Marines. This was made clear to me, a young subaltern in 40 Commando Royal Marines in Malta in 1957, when the Governor, Major General Sir Robert Laycock, visited us. Our commanding officer, and many of the majors and captains had served in commandos in the Second World war, which had ended a mere twelve years before. They all held ‘Lucky’ Laycock in high esteem. As none of us was insubordinate enough to address him thus, we did not know that he disliked the nickname for its insinuation that he owed his position to luck rather than merit. One could argue that in many cases luck in the form of opportunity recognized and seized is one of the attributes of a good commander, and in that sense Laycock was both lucky and a good commander. The notice asking for volunteers to join the Commandos coming out just before he was due to leave Britain for a posting in Egypt; his escape and evasion after the abortive ‘Rommel Raid’; and his appointment to succeed Mountbatten as Chief of Combined Operations are just three examples of how the wings of Laycock’s luck beat over his head on numerous occasions.

He was most certainly not lucky to be sent to command the commandos of Layforce in the Middle East; although only the gift of foresight could have told him that. That they were misused was not his fault; anymore than the debacle in Crete, in which Layforce was involved at the very end, was his fault. Given a choice, and again equipped with a crystal ball, he would probably have opted for command of one of the four Special Service (Commando) brigades in the more fulfilling period of late 1943 onwards. But other than a very successful twelve days commanding the Special Service Brigade in Sicily and Italy in mid-1943, this was not to be. His appointment as CCO put paid to that. But the beneficiaries of the decision to make him CCO were the commandos, and especially the Royal Marines. The frustrating time experienced by the Royal Marines during the first half of the Second World War is given due coverage by Richard Mead. The Admiralty were the architects of the muddle and frustration and to some extent a few senior Royal Marines were as well. Mountbatten and Laycock saved the Royal Marines from the oblivion that would have been their fate after the Second World War. In his foreword to the Green Beret: The Story of the Commandos, Mountbatten refers to Laycock as ‘one of the original Commando soldiers – and in my opinion perhaps the greatest of them all’. That accolade, written in 1949, surely refers not just to Laycock’s achievements in action, but even more so to his work as CCO from mid-October 1943 to June 1947. It is fitting that it does so.

Several well known personalities appear in the book, among them Evelyn Waugh whom Laycock allowed to serve in the Special Service Brigade, in the role of court jester, long after he had overstayed his welcome. Several officers who served with him have expressed the view that although personally brave, Waugh was the type of officer who should never be allowed near troops.

Commando General is a balanced and perceptive biography of a soldier whose work endures to this day. It is also a window on a world that has all but disappeared, and the glimpses we are given are entertaining and revealing. The author is to be congratulated on a very enjoyable and informative work, which moves along apace.

Julian Thompson

Introduction

In early June 1940 Great Britain was on the back foot. The British Expeditionary Force had been ejected from the continent of Europe and, although the majority of its men had been rescued, all its heavy weapons and transport had been abandoned at Dunkirk. France, the country’s only ally outside the British Empire, was a broken reed and would shortly capitulate to the Germans. The prospect of invasion seemed all too likely and, unsurprisingly, the focus of the armed forces was exclusively on defence.

Winston Churchill, Prime Minister for just a month, was determined to find some way to take the battle to the enemy rather than simply wait to be attacked. The main obstacle was water. Germany was already in control of the coastline of Europe from North Cape to the Pas-de-Calais and would shortly extend its rule to the Spanish frontier. The chances of crossing the intervening seas in significant strength in the immediate future were minimal, but Churchill saw an opportunity for small-scale operations to show the ene

my that he was not safe in Fortress Europe but could be attacked at any time. He demanded from his military leaders a force which could mount frequent raids on that long coastline.

Thus were born the direct ancestors of today’s 3 Commando Brigade, an elite formation which has continued to prove itself since the Second World War, in Korea, at Suez, in the Falklands, Iraq and Afghanistan and a number of other smaller campaigns.

However, whilst a very small number of Royal Marines were recruited into the original Commandos in mid-1940, the new force was essentially an Army affair, and it was not until early in 1942 that the first RM Commando was formed. Amongst the officers selected to raise the Army Commandos was a thirty-threeyear-old captain in the Royal Horse Guards, Robert Laycock. Just over three years later he would become the youngest general officer in the British Army and the Chief of Combined Operations, sitting at the head of the organization which, more than any other, made possible the landings which put the Western Allies back in strength onto the continent of Europe.

I have long been fascinated by Bob Laycock’s wartime career. The eighteen months which followed his selection to raise 8 Commando were for the most part a story of disappointment, failure, even disaster. Yet in early 1942 he was appointed to the most senior position within the overall Commando force and, following a short period of active service in 1943, was the surprise choice to follow Lord Louis Mountbatten at Combined Operations. I decided to look more closely at how this rapid elevation had been achieved.

I knew before I began that Bob had left behind some potentially very useful material, which was deposited in the Liddell Hart Archives at King’s College, London. These papers turned out to be voluminous, containing mostly official and semi-official documents, but also many of a more personal nature. When I approached his surviving children, who were supportive from the outset, they told me that he never threw anything away, a trait which I, as a biographer, could only thoroughly commend!

It turned out that a lot of other important papers had been retained by the family. Bob only kept a proper diary during the early years of his military career, initially as a cadet at Sandhurst and then as a subaltern in the Royal Horse Guards; at first glance it is of rather more interest to a social historian than a military one, but on a closer look it is indicative of the level of professionalism, or lack of it, in the British Army in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The diary of his voyage in a four-masted barque around the Cape of Good Hope in 1932, whilst on extended leave from his regiment, is fascinating and throws a great deal of light on his character.

The most exciting find, however, was his draft memoirs. These were unearthed only shortly before I began to write, which in retrospect was a very good thing as I might otherwise have been tempted to skimp on some of the research. It was known that he was working on them and, indeed, I had found fragments at King’s College; but apparently he thought that they were rather dull and appears to have made no attempt to have them published. The memoirs are, in fact, far from dull. Bob wrote excellent prose, and his keen sense of humour makes them very entertaining. They cover his pre-War career relatively sketchily until he left his regiment in 1937, but thereafter are full of both information and opinion, adding depth to what I had already discovered and correcting a few misconceptions. Unfortunately, they come to an abrupt end in the autumn of 1941, so do not cover some important parts of Bob’s military career, including his participation in the raid on what was believed to be General Rommel’s headquarters in North Africa, his period of active service in Sicily and Italy and his term as Chief of Combined Operations. There are jottings for the missing years in the Liddell Hart Archives, but they take the form of cryptic aide-memoires, which are of little real value. What the memoirs do include of particular significance are his own accounts of his selection for the Commandos and of events on Crete.

The very brief period which Bob spent on Crete, an incident-packed five days in all, was the most controversial of his career. The controversy, however, did not see the light of day until half a century later, long after Bob had died. It emerged in Antony Beevor’s book, Crete – The Battle and the Resistance, published in 1991. The issues were firstly, whether Bob disobeyed orders that Layforce should be the last to be evacuated from the island, and secondly, whether he should have left himself, whilst the majority of his command remained to be taken prisoner. Beevor, whilst stating that there was no question of cowardice on Bob’s part, was critical of his decisions; his view has been repeated in subsequent accounts and has arguably tarnished Bob’s reputation.

Bob, however, has had at least one champion, in the person of Professor Donat Gallagher of James Cook University, who has consistently sought to justify his decisions and actions. The debate between Gallagher and Beevor, largely conducted through articles and letters in various learned journals, depends heavily on the timing of certain events and the interpretation of the interaction between Bob and his superiors. Whilst highly interesting to me, the arguments are likely to be very tedious to most of my readers. I have, accordingly, decided not to set out the two points of view but to make up my own mind on the subject based on the evidence available. I have had the advantage over the two eminent historians of reading Bob’s memoirs, which give a detailed account of the battle and the circumstances of his evacuation. Whether these would have made any difference to Beevor or Gallagher, I cannot say. One might argue on the one hand that they are a primary source, but on the other that they were written many years later, when memory was inevitably less accurate, and that they were specifically designed to be a defence of the decisions taken at the time.

Whilst Bob’s wartime career will be of most interest to readers and thus occupies the greater part of this book, it took up only ten per cent of his life. Inevitably, his family background and his education were important ingredients in making him the man he was. However, there are only a few clues as to how the carefree young subaltern of the late 1920s, seemingly more interested in field sports and social life than in his military duties, developed into the highly professional soldier of the 1940s. One of the most telling documents unearthed for me by the family was a notebook, the front part of which contained Bob’s personal appointments diary for 1942, whilst the back, evidently transcribed from other sources in 1945 and then continued until three days before he died in 1968, listed every book he had read from 1928 onwards. It is clear that, at a time when the average cavalry subaltern would have probably confined his reading to The Field and Tatler, Bob was extraordinarily widely read. In 1928, the year after he joined the regiment from Sandhurst, the list included not only light fiction by John Buchan, ‘Sapper’ and R. S. Surtees, but much more serious works by Bertrand Russell, Sigmund Freud, André Maurois and Basil Liddell Hart. A similar mix continued until the War, during which the balance shifted markedly to the lighter end of the spectrum. The year 1940, for instance, was heavily dominated by P. G. Wodehouse, perhaps unsurprisingly given the background of current events. Although history and biography in particular subsequently reappeared in the reading list, Bob’s taste thereafter, albeit very catholic, remained biased towards fiction.

Bob’s family provided a rock-solid foundation to his life. The major source of information on his forebears was a slim volume published privately in 1936 by his aunt, Barbara Mitchell-Innes, which focused on his father, Joe, but went back some way into previous generations. By an incredible stroke of luck I managed to acquire for myself a copy of the privately printed log of the first major voyage of Joe’s yacht, the Valhalla. Joe was the most important influence on Bob’s early life, and I decided to cover him in some detail in the book, but it is clear from both Mitchell-Innes and Bob’s diaries that his parents, brothers and sisters, aunts, uncles and near cousins were always very close, seeing a great deal of each other both at the family home at Wiseton in Nottinghamshire and in London. Bob himself went on to have a very successful marriage to Angela Dudley Ward, and they and their children remained as close as had previous generations.

Bob Laycock’s main claim to fame remains his role in the creation and development of the Commandos. At the time of his appointment to 8 Commando, few had any real idea of how they were to be employed. As it turned out, they were largely misused during their first two years, a litany of failure only alleviated by a few modest successes, in many ways reflecting the story of the British Army as a whole. Nevertheless, much was achieved during this period, especially in the design of a rigorous training regime, not so different from that of the modern Commandos, and in the devising of techniques for amphibious landings whose implementation came to fruition in the last three years of the War. Bob was at the heart of these initiatives, as he was in the debates which led to a complete reorganization of the Commandos in late 1943 and their transformation from an exclusively raiding force to one which would thenceforward largely act in support of conventional troops. As the post-War Chief of Combined Operations, he was instrumental in the retention and composition of 3 Commando Brigade, which still exists today, albeit somewhat larger in size and enhanced in capability.

Commando General

Commando General